New contact languages

- Working with children who speak Indigenous languages/dialects

- Partnering with family and community

- Working with children’s first language(s)

- Understanding the local context

- The impact of Australia’s history on Indigenous languages

- Resources

- Building on Indigenous children’s strengths

- Which Indigenous languages are spoken where?

- Mapping Indigenous languages

- Traditional languages

- New contact languages

- Englishes

- What is a dialect?

- How children learn Standard Australian English as an additional language or dialect

- A day in the life of …

- The difference between language and literacy learning

- The role of language in learning

- Bilingual schools

- Setting up for success

Some Indigenous children speak new Indigenous contact languages like creoles or mixed languages as their L1. These types of languages have been generated through colonisation by contact between speakers of different languages, such as traditional languages and English-based varieties. Despite their historical influences, new Indigenous languages are separate from any of their source languages.

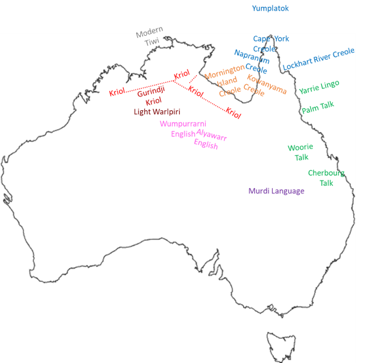

Creoles, a type of contact language, are widely spoken in northern Australia outside of the traditional language speaking communities. The most widely spoken are Kriol on the northern Australian mainland, Yumplatok in the Torres Strait and related varieties on northern Cape York. Mixed languages, such as Light Warlpiri and Gurindji Kriol, have an obvious single traditional language component in their makeup.

New contact languages are ‘Indigenous languages’ because they are spoken almost exclusively by Indigenous peoples and they are spoken in no other country. Like any other L1, a contact language like Kriol or Yumplatok is an integral part of speakers’ identity. Unlike many other languages, however, new Indigenous languages go through a process of recognition, starting out as unrecognised, perhaps even wrongly mistaken as a poor version of a contributing language as reflected in the term ‘pidgin English’.

Awareness raising plays an important role in understanding and responding to these contact language situations. People who speak only SAE, who make up the majority of educators in Australia, are unlikely to understand speakers of contact languages fully or well. And vice versa. Without this recognition, suitable education responses for children speaking contact languages may not be provided.

Children who speak a new contact language as their L1 are L2 (second or additional language) learners of SAE and usually also of their traditional language(s), or, in the case of children speaking mixed languages, Elders might want children to also learn the high, strong, heavy (less like SAE) forms of the traditional language.

You can read and listen to Kriol, the creole language spoken in parts of the Top End, Kimberley and Queensland via:

- visit the large Kriol collection of books held in the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages (LAAL): Kriol collection

Hear some Yumplatok (also called Torres Strait Creole, or sometimes just Creole) recorded by teachers at Cairns West State School in far north Queensland via the videos below.